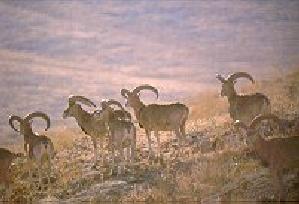

Photos by Okan Arıhan

TURKISH

MOUFLON (Ovis gmelinii anatolica)

Photos by Okan Arıhan

FORMER AND CURRENT DISTRIBUTION

The Turkish Mouflon is a subspecies endemic to Central Turkey. Its

range once covered roughly 50,000 sq. km. in the western and southern parts

of the plateau (Danford & Alston, 1877; Turan, 1984), but following

a decline throughout the 20th century it is now represented by only a single

population of about one thousand individuals at Bozdağ (Konya) (Arıhan,

2000; C.C. Bilgin, pers.obs.).

|

The subspecies is geographically separated from the nominate Armenian Mouflon (O. g. gmelinii) of northwestern Iran and easternmost Turkey. There is no evidence that these two forms were connected at least in the last several hundred years. |

MORPHOLOGY AND OTHER CHARACTERISTICS

Turkish Mouflon differs from the nominate form, most strikingly,

by the absence of horns in females. In addition, the distance between the

horn apexes is much wider than in O. g. gmelinii since the horns

twist backwards with less convergence. The ears and lower parts of throat

are white and the fur is more reddish compared to the nominate form (Kaya,

1991). The color of the Turkish Mouflon varies from pale brown (in summer)

to reddish brown (in winter), and they have white underside and blackish

marks above the knees, most pronounced in the rutting season. Males over

2 years of age show a general darkening in hair color and a ventral neck

ruff (which can grow up to 9-10 cm thick) appear. Older males have a light

saddle that generally starts to form at the age of 3-4 years.

Males weigh between 45-74 kg whereas females weigh around 35-50 kg.

Body length varies between 105-140 cm. (Kaya, 1991). Chromosome number

of the Turkish Mouflon is 2n=54 like other mouflons (Bunch, 1998).

|

|

|

HABITAT AND FEEDING BIOLOGY

Their typical habitat is gently rolling hills in the steppe-forest

ecotone, sometimes of a drier and/or more rugged nature, and usually between

1000 m. and 1500 m. altitude (Kaya & Aksoylar, 1992; Arıhan, 2000).

Typical diet includes steppe grasses and herbs (mainly Anchusa, Brassica,

Erodium, Festuca, Medicago, Thymus) with Erodium tubers consumed

by digging in winter (Kaya & Aksoylar, 1992).

ORIGIN AND TAXONOMY

The form anatolica differs from the geographically separate

nominate form in a number of morphological characters. The division line

between these two forms presumably runs along the Euphrates valley and

the Anatolian Diagonal (an established biogeographic boundary) and is paralleled

in this by a number of pairs of taxa (Turak, 2000). These differences are

generally sufficient to warrant separate subspecific status (OBrien &

Mayr, 1991). Unless genetic criteria based on mtDNA divergence prove otherwise

in the future, the present data would probably also satisfy Evolutionarily

Significant Unit (ESU) status which requires a historical isolation, and

hence, an independent evolution (Moritz, 1994, 1999). The steppic corridor

between central Turkey and western Iran was replaced by deciduous dry forest

or woodland by about 6000 BP (Adams, 1997) possibly acting as a barrier

for the mouflon.

The subspecies isphanica and laristanica of southwest Iran are of apparent hybrid origin (Valdez et al., 1978); unlike those taxa, subsp. anatolica has no sign of a history of hybridization. On the other hand, the island forms musimon and ophion are believed to be the descendants of early domesticated sheep (Masseti, 1997; Hadjisterkotis, 1996). Apart from the fact that females are hornless, there is no evidence for a human-mediated domestic origin. Hornlessness is determined by a single locus, and might have been fixed in anatolica during a past population bottleneck.

Despite recent DNA research (Hiendleder, 1998; K. Byrne, pers. comm.), the ancestry of domestic and Mediterranean (and European) forms is still to be determined. We propose the Turkish Mouflon as one of the most probable ancestors on the basis of its distributional geography, its character of hornlessness, and other characteristics. Research into the phylogenetics of the group is required to solve the problem.

The history of early civilizations in south central Turkey, especially that of Çatalhöyük, also supports such a scenario (e.g. Frame et al., 1999).

CONSERVATION EFFORTS AND REINTRODUCTION

(coming soon)

REFERENCES

Adams J.M. (1997). Global land environments since the

last interglacial. Oak Ridge National Laboratory, TN, USA.

http://www.esd.ornl.gov/ern/qen/nerc.html

Arıhan, O. (2000) Population biology, spatial distribution,

and grouping patterns of the Anatolian Mouflon Ovis gmelinii anatolica

Valenciennes 1856. Unpublished M.Sc..

thesis, METU, 82 p.

Bunch (1998) Diploid chromosome number and karyotype

of Anatolian Mouflon. Report to the Directorate General of National Parks

and

Game-Wildlife Department of Animal

Dairy and Veterinary Sciences, Utah State University, Logan Utah USA

Danford & Alston (1877) The Mammals of Asia Minor,

Proc. Zool. Soc. London, 270-281.

Frame, S., Russell, N. & Martin, L. (1999) Animal

Bone Report. Çatalhöyük 1999 Archive Report, Çatalhöyük Research Project.

Hiendleder, S., Mainz, K., Plante, Y. & Lewalski,

H. (1998) Analysis of mitochondrial DNA indicates that domestic sheep are

derived from

two different ancestral maternal sources:

No evidence for contributions from urial and argali sheep. Journal of Heredity

89(2):113-120.

Kaya, M. A. (1991) Bozdağ (Konya)da Yaşayan Yaban Koyunu,

Ovis orientalis anatolica Valenciennes 1856nın morfolojisi, Ağırlık

artışı,

Boynuz ve Diş Gelişimi. Tübitak Türk

Zooloji Dergisi 15(2). 135-149.

Kaya, M. A. & Aksoylar, M. Y. (1992) Bozdağ (Konya)da

Yaşayan Anadolu Yaban Koyunu, Ovis orientalis anatolica Valenciennes

1856nın

Davranışları. Tübitak Doğa Zooloji

Dergisi. 16(2). 229-241.

Masseti, M.M.G.(1997) The prehistorical diffusion of

the asiatic mouflon, Ovis gmelini Blyth, 1841, and of the bezoar

goat,

Capra aegagrus Erxleben, 1777, in the Mediterranean region

beyond their natural distribution. pp.1-19 in Hadjisterkotis, E. (ed.)

The Mediterranan Mouflon:

Management, Genetics and Conservation.

Proceedings of the second international symposium on Mediterranan Mouflon,

Cyprus.

Moritz, C. (1994) Defining Evolutionarily Significant

Units for conservation. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 9 (10): 373-375.

Moritz, C. (1999) Conservation units and translocations:

strategies for conserving evolutionary processes. Hereditas 130 (3): 217-228.

O'Brien, S.J. & Mayr, E (1991) Bureaucratic

mischief - Recognizing endangered species and subspecies. Science,

251(4998): 1187-1188.

Turak, A.S. (2000) Patterns of species richness, endemism

and rarity in Turkey and their use in conservation evaluation. Unpublished

Ph.D.

thesis, METU, 100 p.

Turan, N. (1984) Türkiyenin Av ve Yaban Hayvanları:

Memeliler, self publication, Ankara.

Valdez, R. Nadler, C.F. & Bunch, T.D. (1978) Evolution

of wild sheep in Iran. Evolution 32:56-72.